Are sodium-ion batteries ready for prime time?

Where Na-ion stands in today's battery ecosystem

Welcome to Lithium Horizons! This newsletter explores the latest developments, companies, and ideas at the frontiers of energy materials. Subscribe below to get the next article delivered straight to your inbox.

Sodium-ion batteries have moved onto the mainstream technology radar. MIT Technology Review named sodium-ion one of its 2026 Breakthrough Technologies, reflecting the growing commercial relevance. The industry has decisively moved beyond proof-of-concept demonstrations and into the early adoption phase, where the technology is being tested at scale across real operating environments.

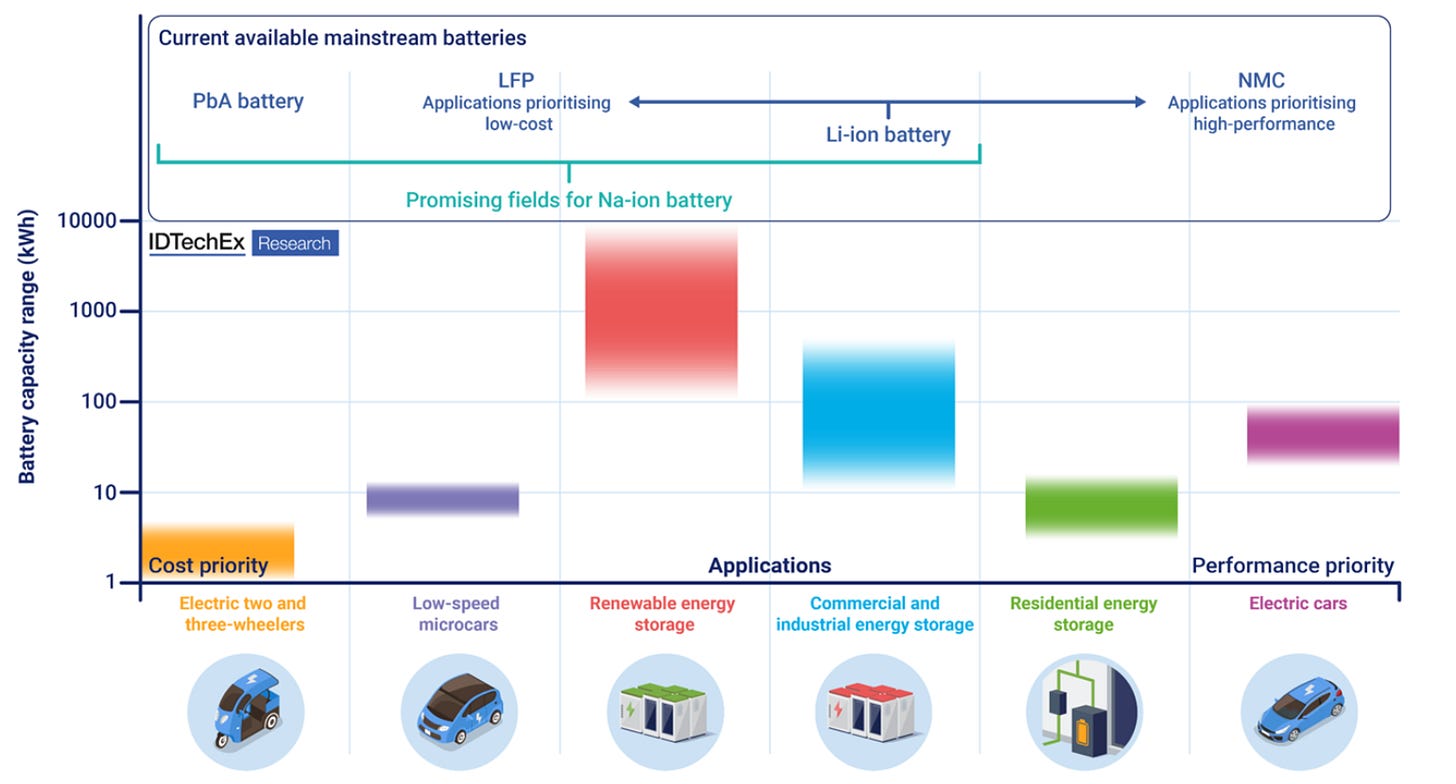

As the global economy accelerates the batterization of anything that can be batterized, it is becoming increasingly clear that no single battery chemistry will dominate all use cases.1 Instead, the future is likely to be multi-chemistry, with different battery technologies optimized for different applications. The key question, then, is what position can sodium-ion batteries secure within that future and where do they offer a meaningful advantage over established lithium-ion technologies.

Sodium vs lithium

Sodium-ion (Na-ion) battery cells closely mirror lithium-ion (Li-ion) batteries in their overall architecture. Both use a cathode and an anode separated by an electrolyte, through which ions shuttle back and forth in a so-called rocking chair mechanism.

The key difference lies in the charge carrier: lithium ions are replaced by sodium ions. Because sodium ions are larger, different electrode materials are required. Commercial Na-ion batteries therefore rely on hard carbon anodes, instead of graphite, and employ several cathode chemistries, including layered oxides, polyanion compounds, and Prussian blue analogues.

This familiar cell architecture allows sodium-ion batteries to be manufactured on existing lithium-ion production lines with modest modifications, shortening scale-up time and reducing capital expenditure.

Moreover, Na-ion batteries benefit from two structural cost advantages:

Abundant, lower-cost precursor materials, practically eliminating exposure to volatile lithium, nickel, and cobalt prices.

Aluminum current collectors on both electrodes, eliminating copper on the anode side.

Together, these factors shift the bill of materials towards a lower cost per kWh compared with conventional Li-ion. In theory, Na-ion cells could be up to ~30% cheaper. In practice, however, current Na-ion cell production costs are around 50–60 EUR/kWh, roughly on par with lithium iron phosphate (LFP), due to immature supply chains and limited manufacturing scale.2

Performance snapshot

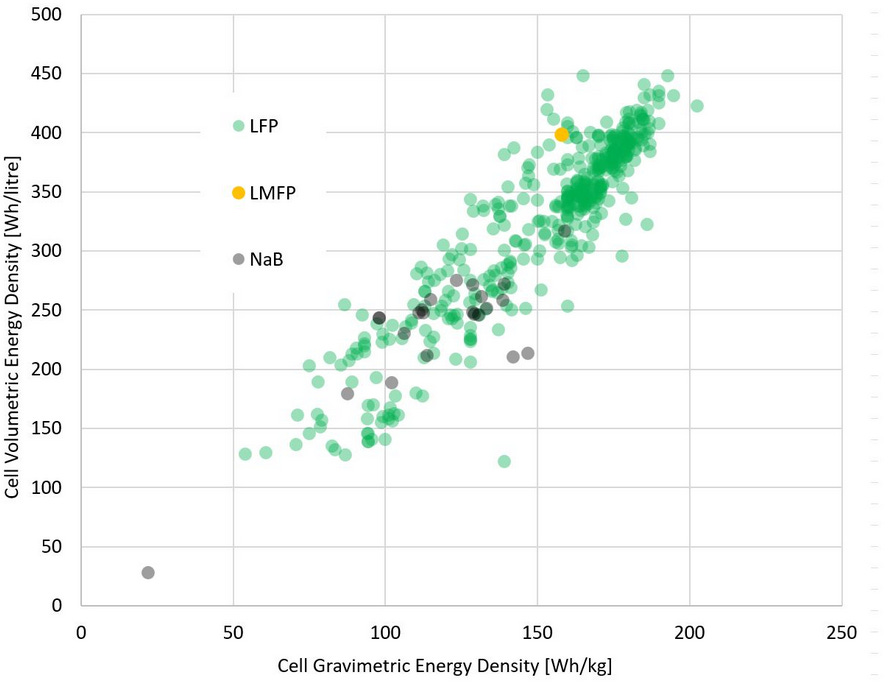

Na-ion battery performance depends heavily on cathode chemistry. Commercial Na-ion cells typically deliver ~100–150 Wh/kg and ~200–300 Wh/l, below mainstream LFP energy density but sufficient for applications where energy density is not critical (Figure 1).

Na-ion batteries also demonstrate a strong low-temperature performance. Compared with many Li-ion variants, they retain both power and usable energy more effectively in cold environments. Operation at temperatures as low as –40 °C is achievable for certain designs, making sodium-ion batteries particularly attractive for cold-climate applications.

In terms of durability, Na-ion batteries routinely achieve several thousand charge–discharge cycles, and under specific chemistries and operating conditions can match or even exceed the cycle life of Li-ion batteries.

From a safety perspective, Na-ion chemistries generally exhibit a lower propensity for thermal runaway than Li-ion batteries. Some sodium-ion cell designs can be shipped at 0 V, practically eliminating the risk of fire.

Commercial status

Na-ion batteries frequently appear in the news alongside claims of technical and commercial breakthroughs. Some of the recent news are listed below:

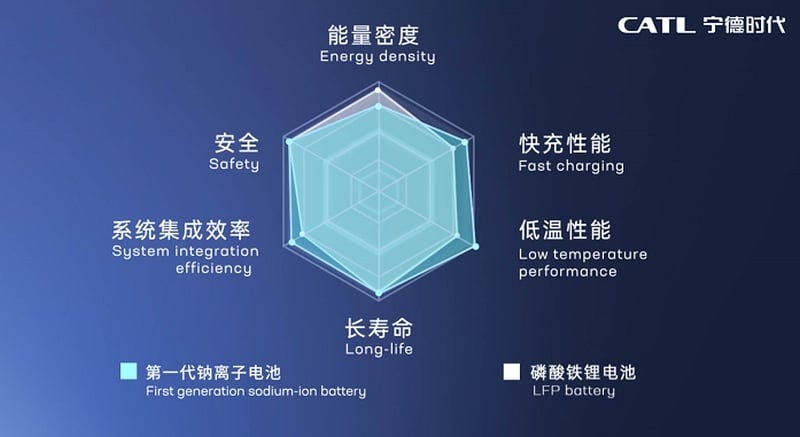

CATL launched its Naxtra brand, marketed as the world’s first mass-producible Na-ion battery for electric vehicles. The cells are claimed to reach ~175 Wh/kg, operate across a wide temperature range from –40 °C to +70 °C, retain up to 90% usable power at –40 °C, and achieve up to 10,000 charge–discharge cycles, while relying on non-flammable materials (Figure 2).

UNIGRID has progressed from pilot production to commercial deliveries of Na-ion battery cells designed for stationary storage. The cells are rated for operation between –40 °C and +60 °C and target cycle lives of 10,000 cycles.

Peak Energy is piloting a grid-scale Na-ion energy storage system in Colorado, with its 3.5 MWh installation positioned as offering the lowest operating cost among commercially available energy storage technologies.

HiNa has introduced Na-ion batteries for commercial vehicle applications, including cells with energy densities of approximately 165 Wh/kg and fast-charging capability, reportedly reaching full charge in around 20 minutes.

Yadea has launched electric scooter models powered by Na-ion batteries with energy densities of approximately 145 Wh/kg and a cycle life of around 1,500 cycles, marking one of the first consumer mobility deployments.

BYD began operations at its 30 GWh sodium-ion battery manufacturing facility in July 2025, signaling large-scale industrial commitment to the chemistry.

Taken together, these developments indicate that Na-ion batteries have moved beyond laboratory research into early commercial deployment. At present, Na-ion cells are available in limited but growing volumes, with initial adoption concentrated in stationary energy storage and cost-sensitive mobility applications, rather than mainstream long-range electric vehicles.

Application areas

Low-cost mobility represents the most immediate opportunity. In segments where price matters more than maximum energy density, such as electric scooters, e-bikes, and rickshaws, Na-ion batteries can rapidly displace lead-acid (PbA) systems. Some Na-ion designs supports fast charging and delivers three to four times longer cycle life than PbA. At the same time, Na-ion cells with an energy density of around 150 Wh/kg, are sufficient to enable 200–300 km of range in low-cost commuter cars, meeting the practical requirements of these markets.

Another key application area is stationary energy storage, particularly those for utility, commercial, and industrial applications. Because these systems are neither mobile nor tightly space-constrained, Na-ion batteries can compete directly with lithium iron phosphate (LFP) for grid support, backup power, and solar self-consumption. Here, advantages such as cost stability, long cycle life, safety, and strong low-temperature performance can outweigh sodium-ion’s lower energy density (Figure 3).

Finally, Na-ion batteries are well suited to industrial applications, including forklifts, automated guided vehicles, and warehouse logistics robots. In these use cases, predictable duty cycles, fast charging, and indoor operation favor battery chemistries like Na-ion that prioritize cycle life, safety, and total cost of ownership over maximum energy density.

Positioning Na-ion in the current battery ecosystem

Much of the discussion around battery technology is framed around which chemistry might eventually displace lithium-ion. This is a wrong perspective since we are heading towards a multi-chemistry future where different chemistries coexist. Such a dynamic is already evident today in the coexistence of lithium nickel manganese cobalt oxide (NMC) and LFP Li-ion batteries.

Viewed through this lens, a more compelling value proposition of Na-ion batteries is their complementary ability to reduce logistical and geopolitical friction across the battery value chain. Many designs of Na-ion batteries rely on abundant, widely distributed materials, reducing exposure to concentrated supply chains. This makes Na-ion batteries particularly appealing for governments and manufacturers seeking technological sovereignty, as they can mostly be produced without relying on geopolitically sensitive minerals.

These features position Na-ion batteries as strategic complement to Li-ion, with Na-ion batteries lowering energy storage dependence on critical minerals, diversifying the battery supply chain, and aligning with government objectives around technological sovereignty. For this reason, Na-ion adoption is likely to be policy-supported rather than purely market-driven, at least in its early stages and particularly if lithium prices remain low.

That being said, Na-ion batteries are well positioned to completely displace PbA batteries across a wide range of micro-mobility applications and is on track to become the dominant battery techology in applications, where cost, safety, and local manufacturability matter more than maximum energy density.

That’s all for now — until next time! 🔋

If you enjoyed this piece, consider sharing or subscribing to Lithium Horizons. It helps support future articles on materials powering the energy transition.

The continuing electrification and transition to renewables, necessitates a way to decouple energy generation and usage. Batteries are the best technology we have to do that, which means that we will continue to see their increased used; hence the term batterization.

A common error in reporting battery costs, is conflating costs vs prices. Cost is what it takes to produce a battery (materials, labor, manufacturing), while price is what the customer pays to buy it, which in addition to costs includes profit margins and other overheads.

Good