The quiet crisis of graphite

Why graphite is the bottleneck in the battery trade war

Welcome to Lithium Horizons! This newsletter explores the latest developments, companies, and ideas at the frontiers of energy materials. Subscribe below to get the next article delivered straight to your inbox.

In late 2023, the global energy market was shaken when China, which is responsible for refining more than 90% of the world’s graphite into battery-grade anodes, announced export controls on the mineral. While the world has been obsessing over lithium, a quieter and arguably more dangerous crisis was unfolding.

The West has poured hundreds of billions of dollars into electric vehicles and battery gigafactories. Yet it remains almost entirely dependent on a single country for one material that no lithium-ion battery can function without: graphite.

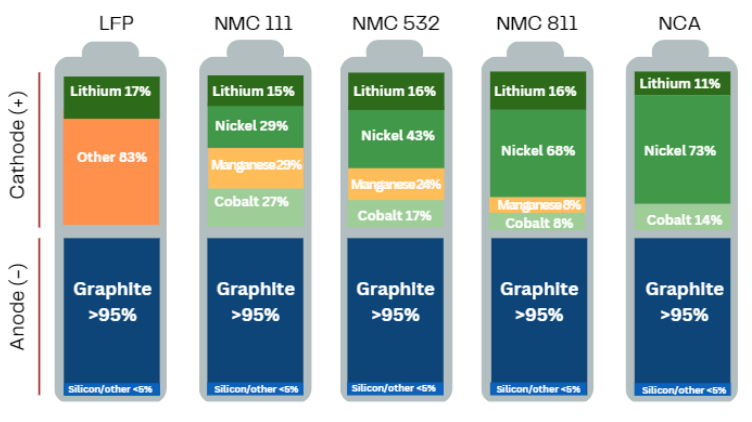

Often overshadowed by its flashier peers (e.g., lithium and nickel), graphite is the workhorse of the battery industry. Every lithium-ion battery, from smartphones to grid-scale energy storage, relies on graphite as the dominant anode material.1 Roughly 95% of the anode material in today’s batteries is graphite and, by weight, a battery cell contains up to ten times more graphite than lithium (Figure 1). Without graphite, lithium-ion batteries simply would not work.

And batteries are only part of the story. Around 40% of global graphite consumption goes into steelmaking. It is also used in high-temperature crucibles, dry lubricants, conductive brushes for electric motors, rocket nozzles, heat shields, and, most famously, pencils. From the furnaces of the steel age to the batteries of the electric age, graphite has remained indispensable.

Geopolitical considerations

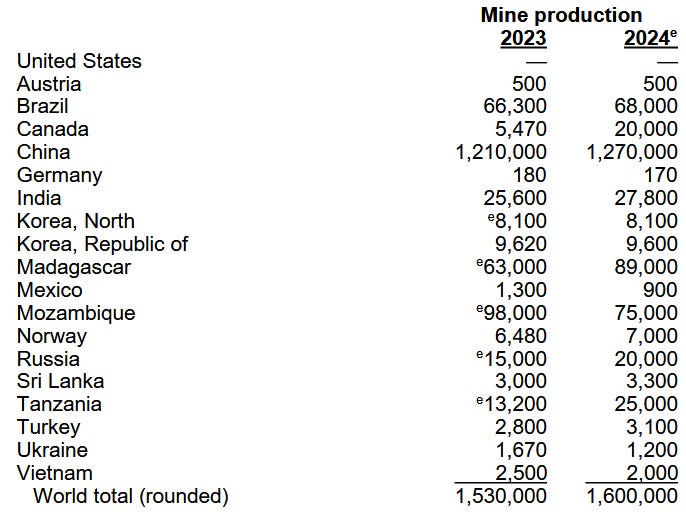

Graphite’s supply chain is far more concentrated than lithium’s, creating a strategic vulnerability that is only now being fully appreciated.

Today, China controls nearly every critical link:

>70% of global natural graphite mining (Figure 2)

~95% of the synthetic graphite production

>90% of battery-grade anode processing

This concentration gives China immense geopolitical leverage. In late 2023, Beijing introduced permit requirements for certain graphite exports. In October 2025, these measures escalated with Announcement No. 58, targeting not just material exports, but also the specialized furnaces, equipment, and technical know-how required to manufacture high-performance anodes.2

Although these restrictions were temporarily suspended in December 2025, the suspension expires in November 2026. The West now has less than a year to build meaningful domestic capacity before the supply is once again constrained.

It raises an uncomfortable question: what if the energy transition isn’t limited by lithium, but by the same material found in your pencil?

In this article, we examine:

Why graphite is indispensable to lithium-ion batteries

The processing technologies China is protecting

Graphite projects emerging outside of China

Potential alternatives that could weaken the graphite monopoly

Let’s dive in! 🔋

NOTE: If you are reading this in your email client, the text may be clipped due to its length. Click on “View entire message” at the bottom of your email to read the whole article, or open it in your browser or Substack app.

Graphite 101

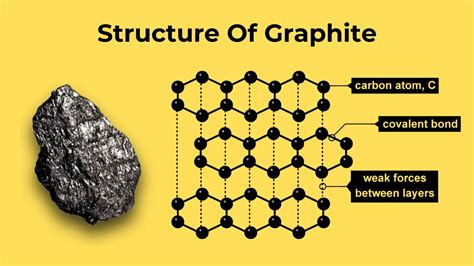

Graphite is a naturally occurring crystalline form of carbon. Depending on the atomic arrangement, carbon can form many allotropes (e.g., graphene, carbon nanotubes, fullerenes, etc.), each with radically different properties.

Graphite consists of carbon atoms arranged in flat, hexagonal sheets stacked on top of one another (Figure 3). The bonds within each sheet are strong (i.e., covalent), but the forces between sheets are weak. This layered structure explains graphite’s seemingly contradictory properties: it is soft and slippery like a lubricant, yet electrically and thermally conductive, chemically stable, and capable of withstanding extreme temperatures.

This rare combination allows graphite to bridge legacy industries and cutting‑edge technologies, making it as useful in a blast furnace as it is inside an EV battery.

Why graphite works so well in batteries

In a lithium-ion battery, graphite serves as a host material. During charging, lithium ions migrate from the cathode and intercalate between graphite’s layers. Other materials can perform this function, but graphite remains dominant for several reasons:

Structural stability: During lithium intercalation, graphite expands by only ~10% in the direction perpendicular to the surface of its layers, allowing batteries to survive thousands of charge-discharge cycles without cracking.3

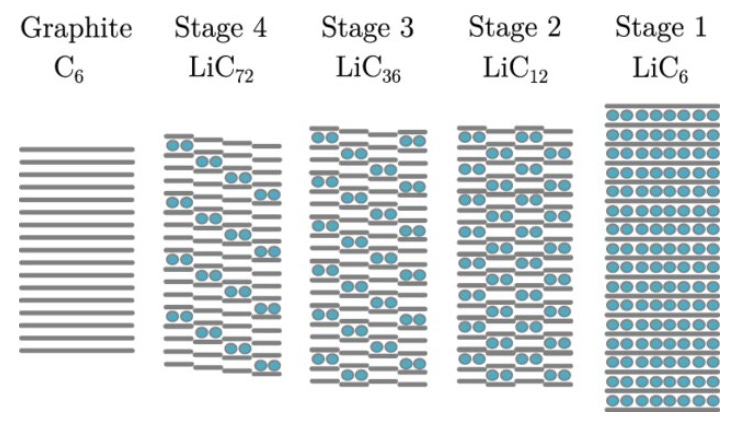

High capacity: At full charge, graphite reaches the composition LiC₆: one lithium atom for every six carbon atoms, corresponding to a theoretical capacity of 372 mAh/g. Modern commercial anodes routinely achieve 95–98% of this limit (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Lithium intercalation into graphite proceeds in stages. At full intercalation (LiC6), one lithium ion is present for every six carbon atoms (graphite sheets are grey; lithium-ions are blue). Source: Journal of Energy Storage High electrical conductivity: Electrons move rapidly across graphite’s two-dimensional sheets, enabling high power delivery which is critical for EV acceleration and fast charging.

Low electrochemical potential: Graphite operates at a very low electrochemical potential, close to that of lithium metal. This maximizes the cell’s energy density, enabling more energy to be stored in smaller and lighter battery packs.4

Stable electrolyte interface: At low potential, the electrolyte forms a thin, protective coating on graphite’s surface that allows lithium ions through while preventing further electrolyte breakdown, enabling high efficiency, long cycle life, and safe operation.

This combination of stability, performance, and safety, in addition to low cost, makes graphite exceptionally difficult to displace.

Making battery‑grade graphite

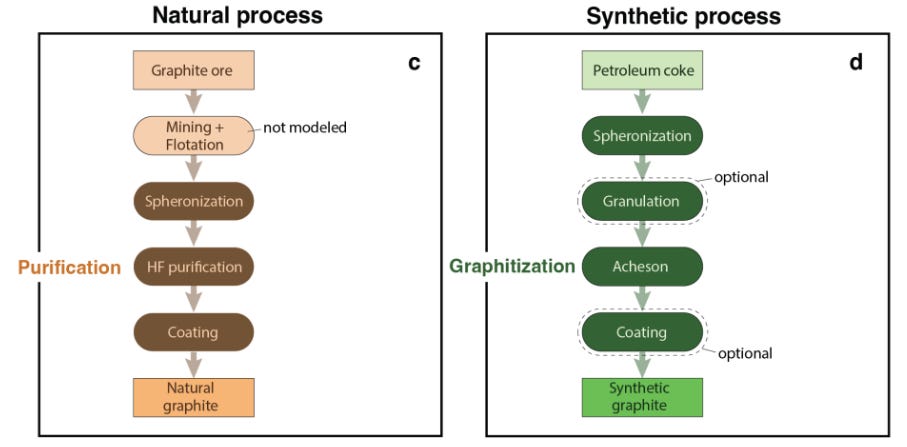

There are two main sources of graphite used in batteries:

Natural graphite, mined from deposits and later purified and shaped.

Synthetic graphite, produced from petroleum coke or coal‑tar pitch through extremely energy‑intensive heat treatment.

Transforming graphite into a battery anode requires a demanding industrial process which can be slightly different depending on whether the graphite is natural or synthetic (Figure 5). Some of these critical processes are:

Purification to >99.9% carbon, as trace impurities can degrade performance or cause safety failures.

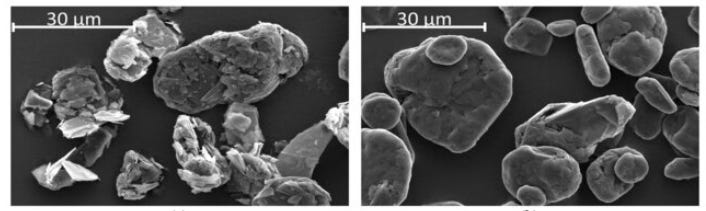

Spheroidization (or spheronization), where sharp flakes are rounded into uniform spheres to improve packing density and consistency.5

Graphitization, heating carbon to temperatures above 2,800 °C so atoms rearrange into perfect hexagonal layers, removing defects.

Surface coating with a thin carbon layer to stabilize the interface with the electrolyte and extend cycle life.

These steps, particularly spheroidization, graphitization, and coating, are where China has concentrated its technical operational advantage. Export controls now explicitly target the equipment and expertise behind these processes.

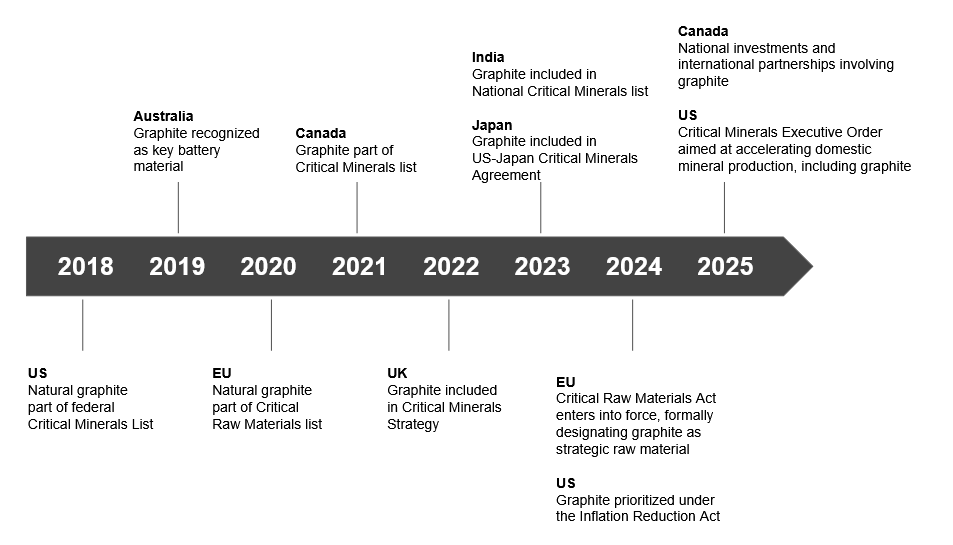

Re-balancing the supply chain

Driven by national security mandates like the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the EU’s Critical Raw Materials Act (Figure 6), a parallel supply chain is being constructed to decouple from China’s dominance. This effort aims to relocate the entire value chain, from extraction to the chemical purification of anode materials.

North America is focusing on vertical integration, owning the mine and the processing facility. The U.S. alone is investing over $10 billion in graphite projects, some of which are listed below:

Nouveau Monde Graphite (Quebec) is constructing the Matawinie mine and Bécancour refinery, with offtake agreements from GM and Panasonic.

Graphite One (Alaska) is developing the Graphite Creek deposit and received U.S. Department of Defense funding to accelerate feasibility work.

Anovion (Georgia) is scaling synthetic graphite production to 40,000 tonnes with Department of Energy support.

Westwater Resources (Alabama) is completing its Kellyton anode plant, backed by SK On.

Novonix (Tennessee) is scaling synthetic graphite production at its Riverside facility to 20,000 tonnes and is developing the Enterprise South site to reach a total capacity of 50,000 tonnes by 2028.

Unlike North America, Africa and Australia have become the world’s primary alternative for raw high-grade natural flake graphite:

Syrah Resources (Mozambique) supplies its Vidalia anode facility in Louisiana, the first commercial‑scale U.S. producer of active anode material, with graphite from the Balama mine.

Black Rock Mining (Tanzania) partners with POSCO Future M to feed a new Korean processing hub.

Renascor Resources (Australia) aims to become the lowest‑cost producer of purified spherical graphite outside China, with its Siviour mine-to-site project.

International Graphite (Australia) is expanding processing capacity in both Australia and Germany.

European initiatives prioritize environmental standards, using renewable energy and sustainable purification:

Talga Group (Sweden) leverages hydroelectric power for low‑carbon anode production at its Vittangi site.

Vianode (Norway) is scaling synthetic graphite at Herøya.

Carbonscape (New Zealand/EU) produces biographite from renewable wood waste, bypassing traditional mining.

Despite these efforts, economics remain challenging. Chinese overcapacity has suppressed prices, which fell 10–20% in the first half of 2025. Many Western projects depend on government loans and long‑term offtake agreements that prioritize supply security over lowest cost. Not to mention that qualifying graphite from new sources for batteries takes a long time — 3 to 5 years according to some estimates.

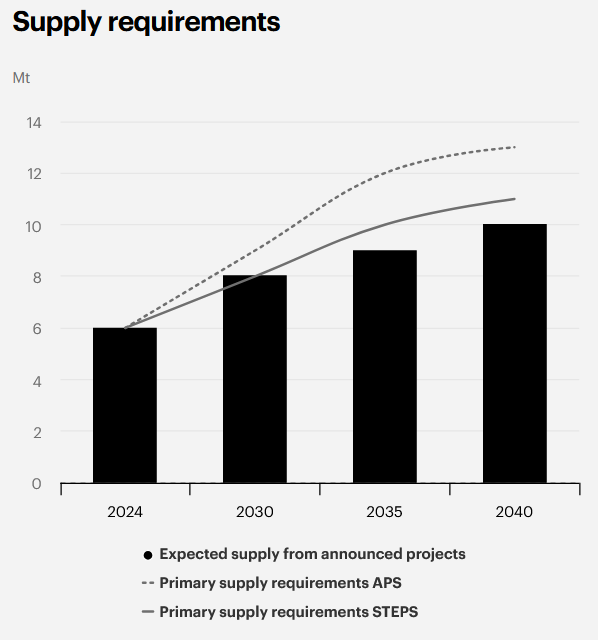

Yet demand remains strong, with graphite consumption projected to grow ~18% annually and creating a deficit by 2030 if new supply fails to materialize (Figure 7).

If not graphite, then what?

Graphite is not the only possible anode for lithium-ion batteries. Laboratories throughout the world have identified numerous possible anodes6, but industry focus has narrowed to two: silicon and lithium metal.7

The most immediate threat to graphite’s dominance is silicon. While graphite is limited to a theoretical capacity of 372 mAh/g, pure silicon can reach roughly 4,000 mAh/g. This is however accompanied by a massive ~400% volume change during charging, which cracks the anode. The way to mitigate this is to use small silicon particles embedded in some protective material, however, this process is extremely expensive. So most high-performance EVs use only 5–10% silicon blended into graphite, capturing some benefits without catastrophic degradation.

Companies like Group14, Sila Nanotechnologies, and Amprius are commercializing silicon‑carbon composites, with some marketed as “graphite‑free.” These technologies are promising, but remain costly and challenging to scale.

Further out lies the lithium metal anode, often paired with solid‑state electrolytes. While pursued by players such as Toyota, QuantumScape, LG Energy Solution, and Samsung SDI, mass‑market deployment is unlikely before 2030.

No magic switch

The uncomfortable reality is this: we cannot innovate our way out of the graphite bottleneck by 2026.

Silicon is still a supporting actor, not a lead replacement. Solid-state batteries remain a horizon technology. For the foreseeable future, lithium-ion batteries—and by extension the energy transition—depend on graphite.

As of 2026, the West does not lack the scientific knowledge to produce battery-grade graphite. It also does not lack intent: mines, refineries, and anode plants are already being built. What it lacks is time.

Building a mine-to-anode supply chain takes years. Permitting, qualification, ramp-up, and cost optimization cannot be compressed by policy alone. Even with aggressive investment, meaningful independence from China will not arrive anytime soon. The future lies in a diversified supply chain. This is the reality check that must inform how we deploy capital, and design battery strategies.

That’s all for now — until next time! 🔋

If you enjoyed this piece, consider sharing or subscribing to Lithium Horizons. It helps support future articles on materials powering the energy transition.

Battery consists of one or more cells. Each cell consists of two electrodes, anode and cathode, sandwiching a conductive liquid or solid called electrolyte. By convention, the anode is the ‘‘negative electrode’’. When the battery is fully charged, it holds the lithium ions; when the battery is used (discharged), these ions and their stored electrical energy flow out of the anode to power the device.

China’s 2023 graphite restrictions were largely a response to U.S. curbs on advanced semiconductors. In contrast, the October 2025 escalation is a more strategic defense of China’s industry ensuring that high-performance anode production remains anchored in China.

One of the reasons why silicon anodes have not been able to fully displace graphite is that they swell up to 400% when hosting lithium, therefore cracking and causing poor energy retention when repeatedly charged and discharged.

Graphite has a low potential without the safety risks associated with pure lithium metal. From energy maximization point of view, the best anode for lithium-ion batteries is lithium metal. However, using lithium metal introduces many safety challenges and energy loss with repeated charge-discharge.

Scanning electron micrograph of flake (left) vs spheroidized (right) graphite from 10.3390/batteries9060305. Notice the lack of sharp edges on spheroidized graphite

I have, for example, worked on phosphorus anodes as a potential replacement for graphite. Examples: https://doi.org/10.1039/C7RA06601E and https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelechem.2022.116852

You could argue that sodium-ion would resolve our issues with graphite geopolitics and you would be somewhat right. Adopting sodium-ion shifts the supply chain to graphitized biomass carbon, instead of graphite, fundamentally changing the geopolitical map. However, sodium is not a 1:1 replacement for all applications using lithium-ion batteries.