Designing batteries for space exploration

The challenge of designing batteries for the Europa Lander mission

Welcome to Lithium Horizons! This newsletter explores the latest developments, companies, and ideas at the frontiers of energy materials. Subscribe below to get the next article delivered straight to your inbox.

“Space, the final frontier… to boldly go where no man has gone before.”

— Captain James T. Kirk, Star Trek

Just as Captain Kirk dreamed of exploring the unknown, engineers dream of powering spacecraft for unknown environments. Space exploration often involves missions to some of the universe’s most inhospitable regions, making robotic spacecraft essential. These spacecraft require reliable power sources, typically provided by energy generators such as photovoltaic solar arrays or radioisotope thermoelectric generators. However, energy generation alone is not always sufficient, particularly during peak power demands. For this reason, energy generators are usually paired with energy storage systems, such as batteries.

Batteries can be categorized as either primary or secondary. Primary batteries are designed for a single use, providing power without recharging, which makes them ideal for space missions where no additional energy generation or storage is available. Examples of planetary probes that used lithium–sulfur dioxide (Li–SO₂) primary batteries include the Galileo and Cassini spacecraft.

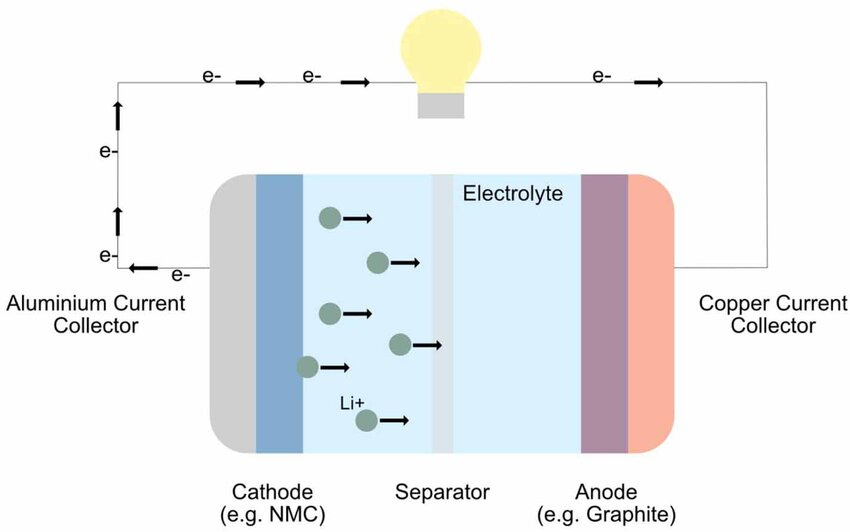

Conversely, secondary batteries are rechargeable (e.g., lithium-ion; Figure 1), allowing them to undergo multiple charge–discharge cycles. This capability makes them suitable for extended space missions that require long-term, sustainable energy storage. The European Space Agency's experimental Proba-1 Earth-observation mission in 2001 was the first to use rechargeable lithium-ion batteries in space.

What constraints do batteries face in extreme environments? How do they differ from those used in everyday applications such as smartphones or electric vehicles? How are they designed, and who manufactures them? These are some of the key questions addressed in this article.

We begin by examining the harsh conditions batteries must endure in space, followed by a brief history of batteries used in space missions, along with their performance requirements and design considerations. We conclude with a discussion of spacecraft designed for Europa missions and an overview of companies that manufacture batteries specifically for space applications.

Let's dive in! 🔋

NOTE: If you are reading this in your email client, the text may be clipped due to its length. Click on "View entire message" at the bottom of your email to read the whole article, or open it in your browser or Substack app.

Extreme conditions

Energy storage requirements for space exploration vary depending on the destination and the nature of the mission. Nevertheless, these systems must consistently withstand a range of severe environmental conditions such as extreme temperatures, radiation, microgravity, and vibration, all while providing sufficient power and energy output.

To appreciate the severity of these conditions, consider the planet Venus. Landing a rover on its surface would require an energy storage system capable of functioning at approximately 500 °C under about 90 atm of pressure. These conditions are roughly 20 times higher in temperature and 90 times greater in pressure than the standard operating limits of commercial lithium-ion battery systems.

Extreme pressures pose significant challenges for the structural design of battery packs. While moderate pressure can improve interfacial contact between the layers of a battery cell, excessive pressure can hinder ion transport, ultimately reducing battery cycle life.

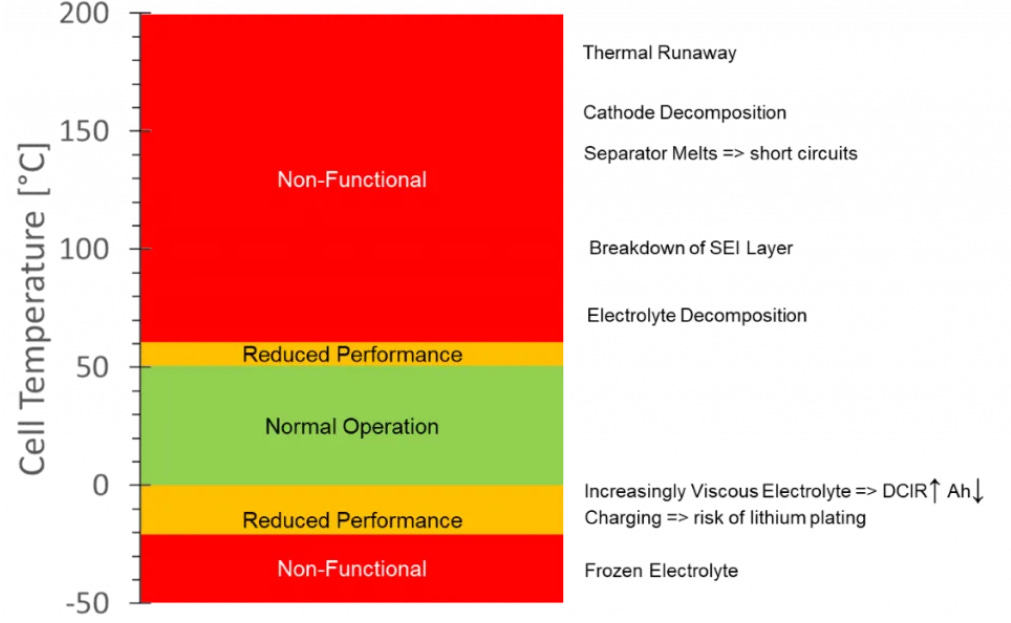

Standard lithium-ion batteries operate optimally between 10 °C and 40 °C. Temperatures outside this range result in degraded performance. At low temperatures, increased electrolyte viscosity and slowed reaction kinetics raise internal resistance and elevate the risk of electrical shorts. At high temperatures, electrolyte degradation, separator melting, and eventual cathode decomposition can occur. The release of oxygen during cathode breakdown can initiate thermal runaway, leading to catastrophic battery failure.1

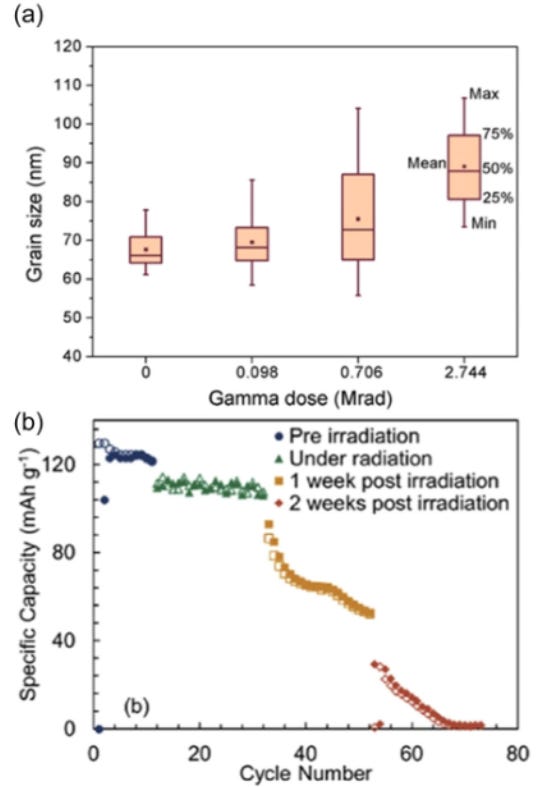

Beyond temperature and pressure, radiation is another critical factor. Earth's magnetosphere protects the planet from much of this harmful radiation, but once outside it, spacecraft are exposed to intense irradiation without adequate protection. Radiation exposure can alter material properties, leading to unpredictable and often degraded behavior (Figure 2).

Ionizing radiation, such as gamma rays, can damage liquid organic electrolytes by generating free radicals that react with other components within the battery cell. Radiation can also induce cross-linking in polymer binders, compromising the structural integrity of electrodes. Additionally, it may alter the pore structure of polymer separators, affecting their wetting behavior. Neutron or ion irradiation induces defects in the crystal structure of materials. Collectively, these effects can reduce battery capacity, shorten cycle life, modify the solid-electrolyte interface, and increase internal cell resistance.

Mechanical stresses such as vibration, acceleration, and impacts are additional considerations, particularly during liftoff or landing. Vibration can compromise interconnections, including electrode-to-tab welds or terminal-to-busbar connections within a battery module or pack.

Understanding these environmental challenges helps explain why space battery development has always involved trade-offs between energy density, cycle life, and reliability.

A short history of batteries in space

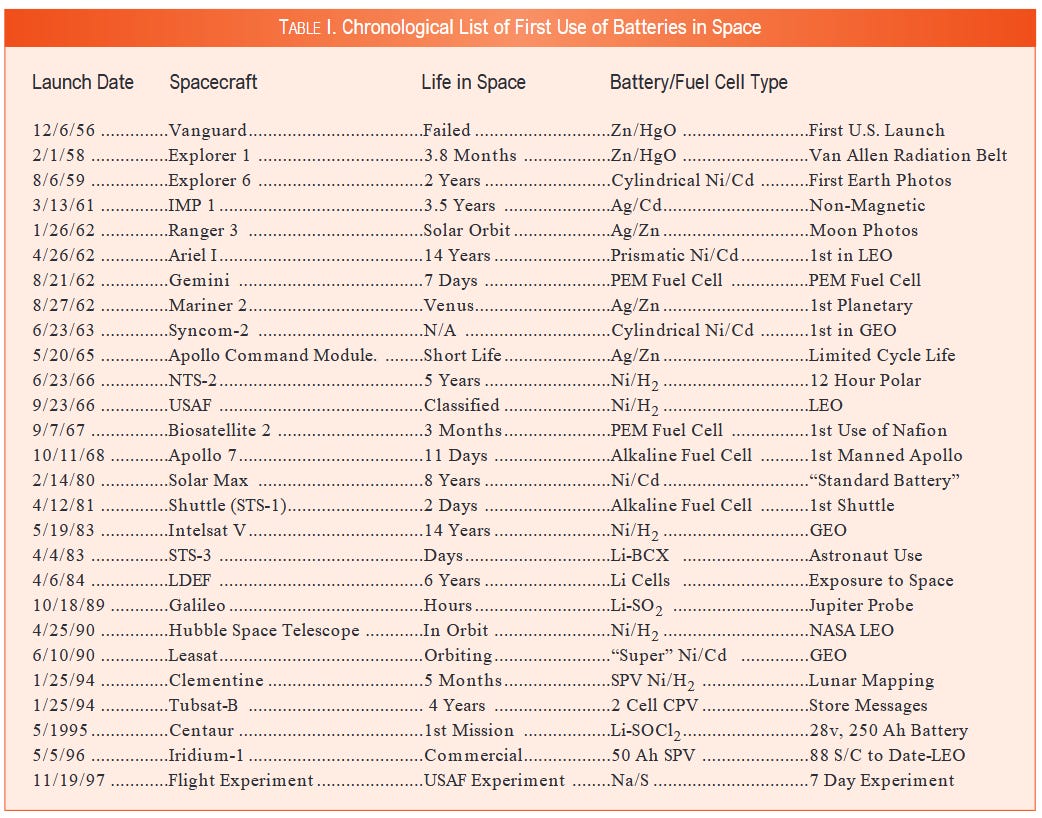

Silver-zinc (Ag–Zn) batteries were the first used in space, on the Sputnik spacecraft launched by the Soviet Union in 1957. These primary batteries had a specific energy of approximately 500 Wh/kg and were used to power communication devices. However, they were soon replaced by nickel–cadmium (Ni–Cd) batteries, which offered a longer operational life of about 2,000 cycles, albeit with a much lower specific energy (~50 Wh/kg). Ni–Cd batteries were first employed on Explorer 6, a NASA satellite launched to study radiation in Earth's upper atmosphere.

Starting in the 1980s, nickel–hydrogen (Ni–H₂) batteries became prominent. Functioning as a hybrid between a battery and a fuel cell, they incorporated a nickel cathode, hydrogen anode, and fuel cell components such as gas-separation membranes and catalysts. These batteries had a specific energy of approximately 50 Wh/kg, but their exceptionally long cycle life (up to 20,000 cycles) made them ideal for demanding space missions like powering the Hubble Space Telescope.

Depending on the mission, other chemistries were historically used (Figure 3). For operations in extreme temperatures, lithium–sulfur dioxide (Li–SO₂) and lithium–thionyl chloride (Li–SOCl₂) batteries are particularly suitable, with operational ranges of –55 °C to 65 °C and –55 °C to 80 °C, respectively.

What about commercial batteries?

While custom batteries were historically necessary, advances in commercial lithium-ion technology now bridge the gap between lab innovation and space requirements. This has led to a growing trend of using off-the-shelf cells for certain space applications, reducing reliance on costly, custom-built batteries.

This shift began with the Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s MarCO CubeSats in 2018, which used Panasonic NCR18650B cells, followed by NASA’s Ingenuity helicopter employing Sony VTC4 cells, and the Europa Clipper mission using LG MJ1 cells. All of these are 18650 cylindrical cells (18 mm diameter, 65 mm height), a form factor that has proven effective for over 30 years.2

Commercial cells offer significant advantages when their chemistry meets the stringent demands of space missions. They are less expensive than custom-built alternatives and come with well-characterized, proven technology. However, mass production often makes modifications for space-specific requirements impractical, and some missions still require fully custom batteries despite the cost and development time.

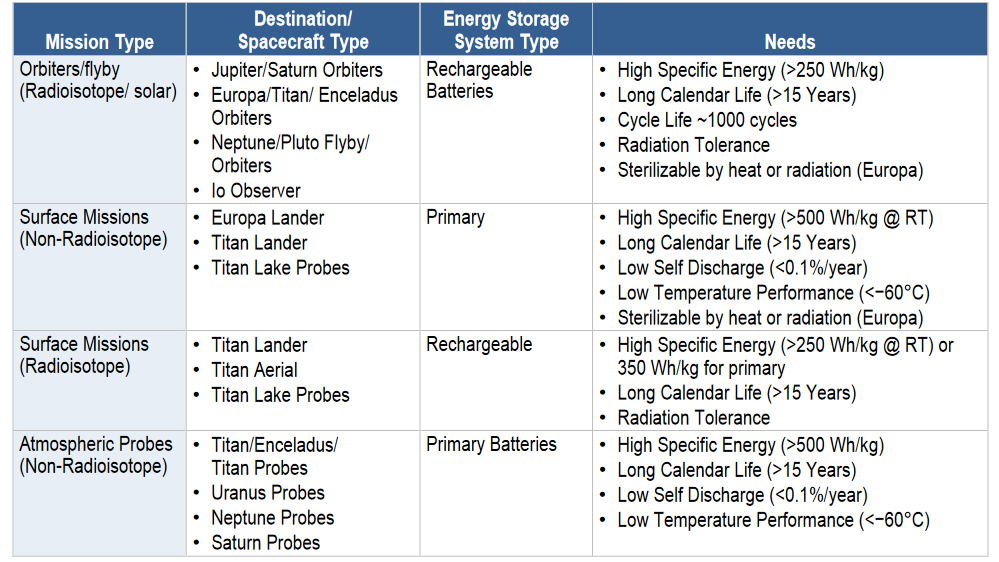

Performance requirements

Space energy storage systems must deliver exceptional performance under strict constraints. Rechargeable batteries must provide more than 250 Wh/kg of energy (Figure 4), near the upper limit of commercial technology. They must also endure over 1,000 charge–discharge cycles and achieve a calendar life (usable lifetime whether in use or storage) exceeding 15 years.

Space batteries are often exposed to extremely cold environments. They must be heated to operational temperatures (e.g., ~20 °C for lithium-ion) via external heaters or self-heating. A common design strategy is to place batteries in thermal contact with the cruise-stage propellant loop, allowing them to reach initial operating temperatures of ~0 °C.

Another important metric is self-discharge, the percentage of energy lost while idle. High-quality lithium-ion batteries typically discharge ~1% per month. High states of charge and elevated temperatures can increase this rate.3

Space battery design

Batteries must endure all environmental conditions during a mission while providing required performance. This involves careful attention to structural integrity, gas generation and venting, pressure differentials, electrolyte leakage, prevention of short circuits, management of extreme temperatures, microgravity, radiation, and over-discharge protection. In short, testing space batteries is much more stringent than testing standard batteries.

Some of the tests that a battery would undergo include:

Electrochemical: The battery is cycled through repeated charge and discharge sequences, including rest periods to simulate idle times. Tests are conducted across different temperatures, currents, and depths of discharge, with internal resistance measured at regular intervals.

Overcharge/Overdischarge: Batteries are deliberately charged beyond their maximum voltage (overcharge) or discharged below their minimum voltage (over-discharge) to evaluate cell behavior and verify that protective circuits engage as intended.

Short-Circuit: For external short circuits, a low-resistance circuit is connected to the battery terminals to confirm activation of the overcurrent protection system. Similarly, for internal short circuits, a phase-change material is inserted between electrodes to artificially induce a short within the cell, testing the battery’s internal safety mechanisms.

Vacuum: Batteries are exposed to pressures below 1% of Earth's atmospheric pressure to check for electrolyte leaks.

Radiation: Batteries are subjected to controlled radiation doses to determine whether capacity loss and internal resistance increases remain within acceptable limits.

Vibration: Batteries are subjected to vibrations at frequencies up to several thousand Hz to ensure they maintain full performance and to detect any physical damage.

The International Organization for Standardization provides guidance through ISO 17546:2024 Space systems — Lithium-ion battery for space vehicles — Design and verification requirements which outlines the tests that should be conducted on space batteries.

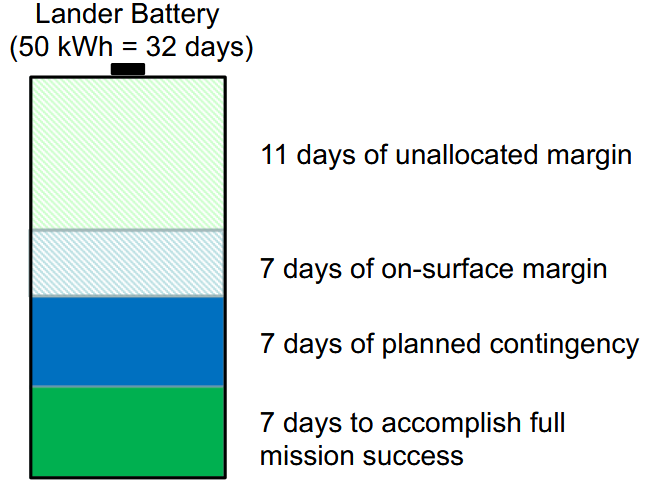

Ultimately, safety margins are incorporated into the battery system to ensure mission success. For instance, the battery for the Europa Lander missions is built to last ~30 days with additional energy reserves to accommodate contingency scenarios (Figure 5).

These safety margins vary throughout the development process but generally ensure that the battery delivers more energy and power than strictly required or operates across a wider temperature range than anticipated. As a result, spacecraft battery systems are typically larger than those used in less critical applications. In space missions, it is far preferable to have a slightly oversized battery than to jeopardize the entire mission with an underpowered system.

Understanding these environmental and performance requirements is essential as NASA plans missions to the most challenging environments in the solar system, such as Europa.

Europa Clipper and Lander missions

NASA’s Europa Clipper mission, launched on October 14, 2024, is on a journey to explore Jupiter's moon Europa. The spacecraft is scheduled to arrive at Europa in April 2030, with its primary goal being to assess the moon’s potential habitability. Over the course of roughly four years, Europa Clipper will perform multiple flybys to investigate the structure of Europa’s ice shell, as well as its geology and chemistry, with the aim of identifying environments beneath the surface that could potentially support life.

The spacecraft is powered by 600 W photovoltaic arrays, which store energy in EnerSys' ABSL lithium-ion batteries. These batteries are configured as three 8S72P (i.e., each module has 8 series strings, and each string contains 72 parallel cells) modules connected in parallel, providing a total capacity exceeding 540 Ah. They are designed to sustain repeated charge and discharge cycles throughout the mission.

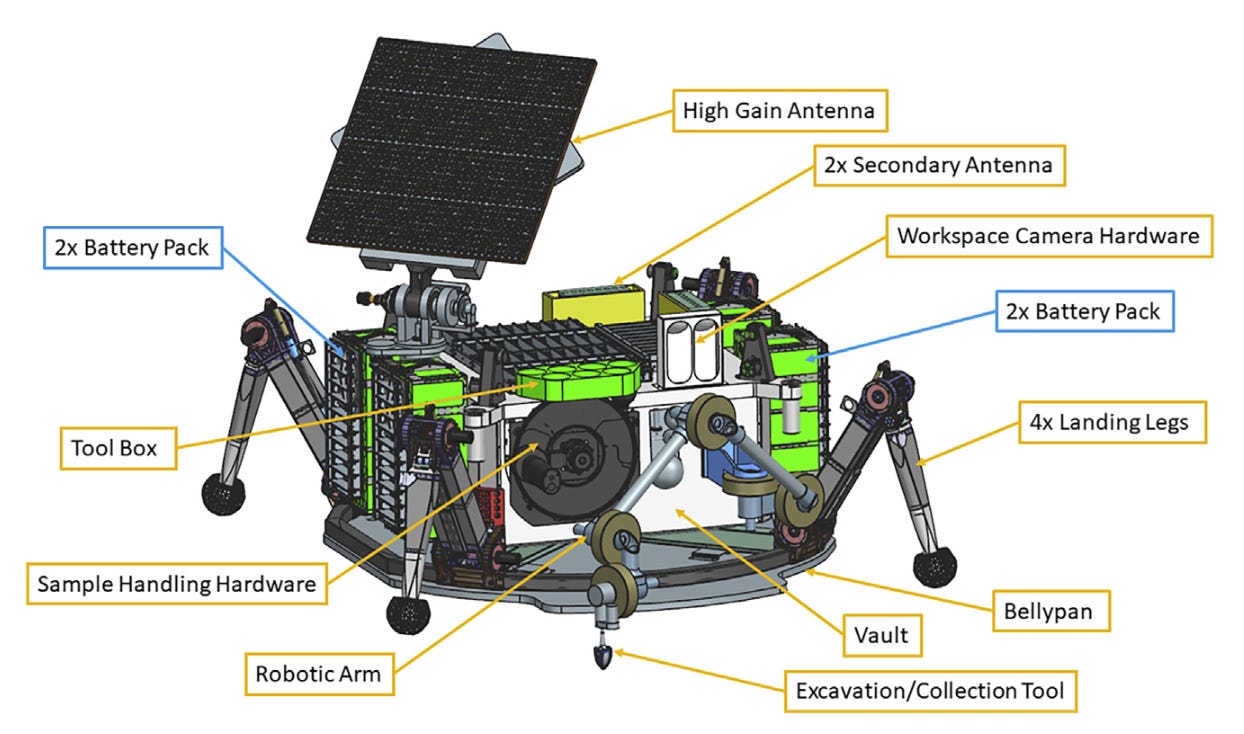

The Europa Clipper mission is set to be followed by the Europa Lander mission, scheduled for launch in 2027. Selecting batteries for a lander on Europa presents several significant challenges. First, Europa receives very little sunlight due to its distance from the Sun, meaning that photovoltaic arrays would need to be prohibitively large to provide sufficient power. Second, Europa’s thin atmosphere exposes the surface to intense radiation, limiting the survival of electronics to just a few weeks and ruling out the use of radioisotope thermoelectric generators; adding adequate radiation shielding would dramatically increase the lander’s mass. Finally, the surface temperature is extremely cold, averaging around –170 °C, further constraining battery choice and design.

Given these extreme conditions, selecting a suitable battery for Europa may seem impossible. However, lithium–carbon monofluoride (Li–CFx) chemistry offers a viable solution. Li–CFx batteries provide a high specific energy of approximately 700 Wh/kg and release about 45% of their energy as heat. By combining insulation with waste heat from the lander’s avionics, the batteries can be maintained at operational temperatures around 0 °C.

Unlike lithium-ion cells, which require recharging and cannot tolerate Europa’s extreme cold and low solar flux, Li–CFx batteries are primary and inherently suited for this environment. They do not require recharging, eliminating the need for solar panels. They also tolerate radiation doses up to 10 Mrad and have a mass of roughly 100 kg for a 50 kWh battery pack (see Figure 6).

NASA is actively developing new battery designs to address the evolving demands of space exploration. These unconventional chemistries drive innovation, impacting not only space applications but also other industries. Conversely, as the commercial battery sector accelerates its own advancements, an increasing number of these new technologies are being adapted for use in space missions.

Companies designing batteries for space applications

Here are several companies that manufacture batteries for space applications:

Saft Groupe: Manufactures lithium-ion battery cells for a variety of space applications including GEO telecommunications, MEO global-positioning satellites, space experiments, launchers, rovers, planetary landers, astronaut tools, and deep-space probes.

SAB Aerospace: Produces battery packs for satellite systems, which include comprehensive management systems like protection circuits, thermal controls, and voltage monitoring.

Eagle Picher: Specializes in lithium-ion batteries and maintains a close partnership with NASA. Their batteries have powered the Mars rovers (Curiosity, Spirit, and Opportunity), missions to Venus and Mars, the Hubble Space Telescope, and the International Space Station.

EnerSys: Pioneered the use of lithium-ion batteries in space. They create batteries for launch vehicles, Earth observation, and interplanetary missions.

Mitsubishi Electric: Focuses on manufacturing lithium-ion batteries to store electric power generated by spacecraft solar arrays.

GS Yuasa: Manufactures battery cells for satellites and spacecraft. By January 2023, the power systems of over 200 satellites relied on GS Yuasa's lithium-ion cell technology.

Conclusion

Space batteries are a testament to human ingenuity, balancing extreme environmental challenges, energy density, and mission-critical reliability. From Ag-Zn to Li–CFx, each innovation illustrates how materials science continues to expand humanity’s reach and power the frontiers of energy.

That’s all for now. Until next time 🔋!

If you enjoyed this piece, consider sharing or subscribing to Lithium Horizons. It helps support future articles on materials powering the energy transition.

Read more

Battery cell is a complicated piece of technology with multiple intertwining phenomena. My experience tells me that lithium-ion batteries operate relatively well in a 10-40°C range. The image below shows that range to be 0-50°C which is a bit of a stretch, however small changes in the materials used can change the operating temperature window of a cell. Nevertheless, the image gives a good general idea of what happens as a function of temperature.

The 18650 cell format was introduced in the 90s. The 21700 was introduced only in 2017. Only three years later, in 2020, Tesla announced the 4680 format. This is a testament to the acceleration that battery industry is witnessing after decades of slow improvements.

State of charge, or SoC, is a metric measured in percentage that describes how "full" a battery is. If it is fully charged, then SoC equals 100%; if it is only half charged, then SoC equals 50%, and so on.