Tesla's batteries: a five-year reality check

The Battery Day 2020: what worked and what didn’t

Welcome to Lithium Horizons! This newsletter explores the latest developments, companies, and ideas at the frontiers of energy materials. Subscribe below to get the next article delivered straight to your inbox.

In September 2020, Tesla hosted its highly anticipated Battery Day. Led by Elon Musk and Drew Baglino, the event outlined a grand plan to rewrite the economics of lithium-ion batteries and unlock a 25,000 USD electric vehicle (Figure 1).

Five years after Battery Day, Tesla’s vision proved directionally right but far harder to manufacture than its timelines suggested. While Tesla successfully industrialized certain manufacturing innovations, many core breakthroughs in materials and cell design remain difficult to scale.

This article examines what Tesla’s Battery Day got right, where execution fell short, and what those outcomes reveal about the battery industry.

NOTE: You can watch the full Battery Day event on Youtube. The transcript of the event can be read here and here.

The original promise

Tesla’s thesis was straightforward: to build a truly affordable EV, battery manufacturing had to be vertically integrated and radically redesigned.

The Battery Day set two headline targets:

Scale: 100 GWh of battery production by the mid-2020s and 3 TWh by 2030.

Cost: A 56% reduction in pack-level costs.

To achieve this, Tesla presented five interconnected innovations:

The 4680 ‘‘tabless’’ format

Shifting from a standard 2170 cylindrical cell to a larger 4680 format (i.e., 46 mm diameter, 80 mm height), Tesla could use fewer cells per pack and larger electrodes, resulting in cheaper assembly. The claim was that this format could deliver 5x more energy and 6x more power per cell.

To solve the heat issues, which are common in larger cells, Tesla introduced a ‘‘tabless’’ design (Figure 2), where the electrode’s entire edge conducts current, lowering resistance and improving thermal dissipation.1 This was also supposed to help in achieving a higher production throughput, since there would be no stopping for traditional tab welding steps.

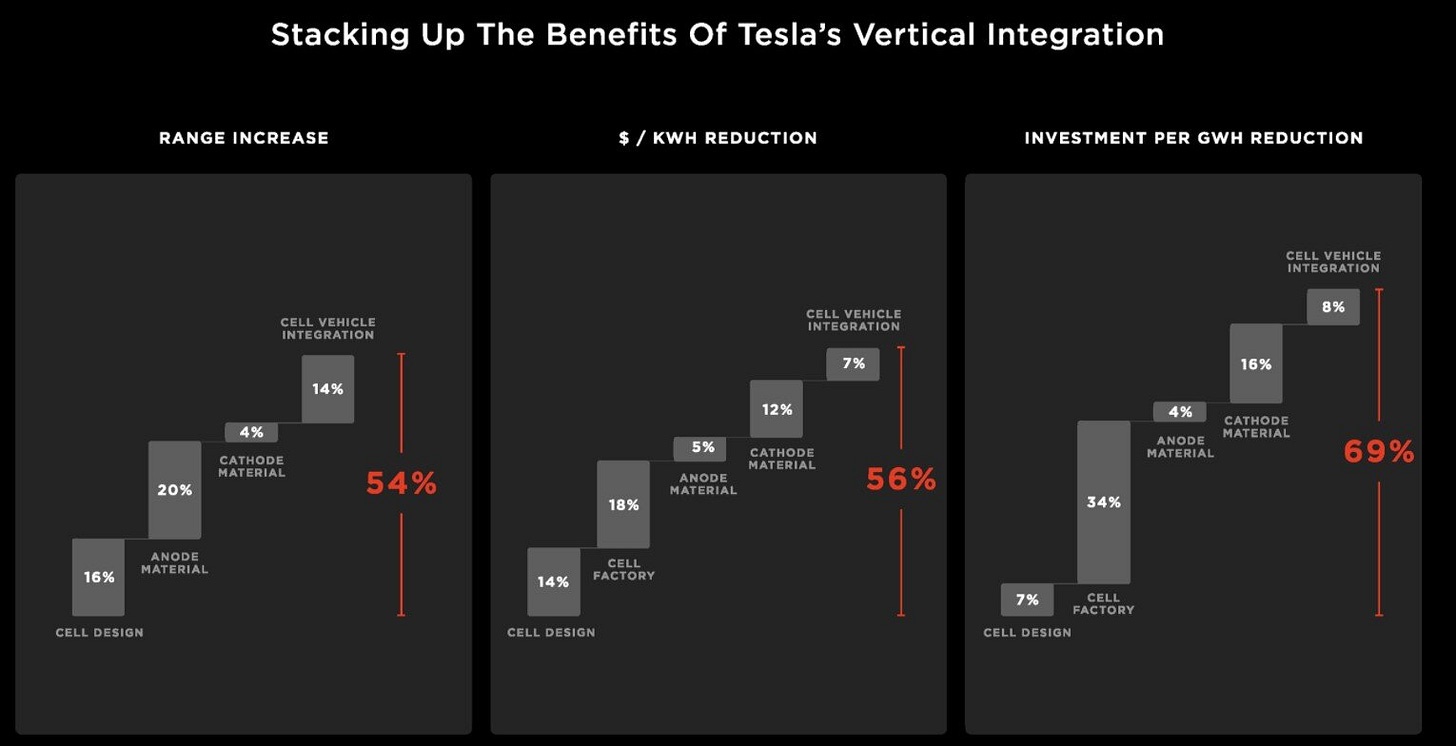

The cell form factor change was expected to allow for a 14% USD/kWh reduction at the battery-pack level.

Dry electrode manufacturing

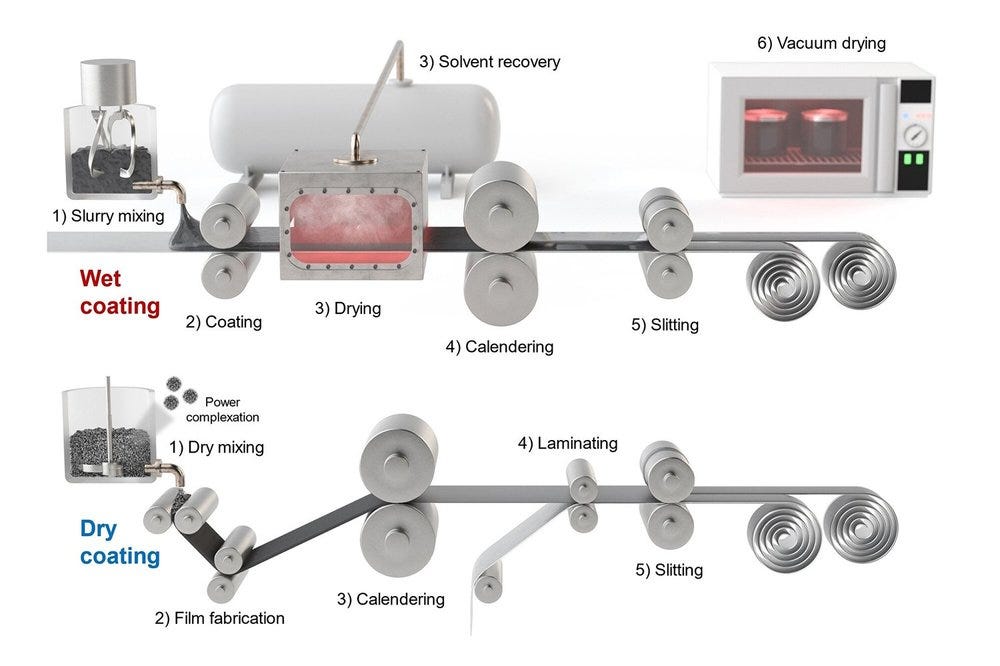

Conventional electrode coating relies on liquid solvent-based slurries (i.e., wet process or coating) and massive drying ovens to evaporate said solvents after coating (Figure 3). By using a dry powder-to-film process (i.e., dry process or coating), Tesla aimed to eliminate solvents, cut factory footprint tenfold and lower energy consumption.

The end goal was a high-speed continuous-motion production line capable of ~20 GWh/year; a massive increase in production output considering that state-of-the-art wet process lines offer ~3 GWh/year per line.

This manufacturing innovation was supposed to enable an additional 18% USD/kWh reduction at the battery pack level.

Silicon-rich anode

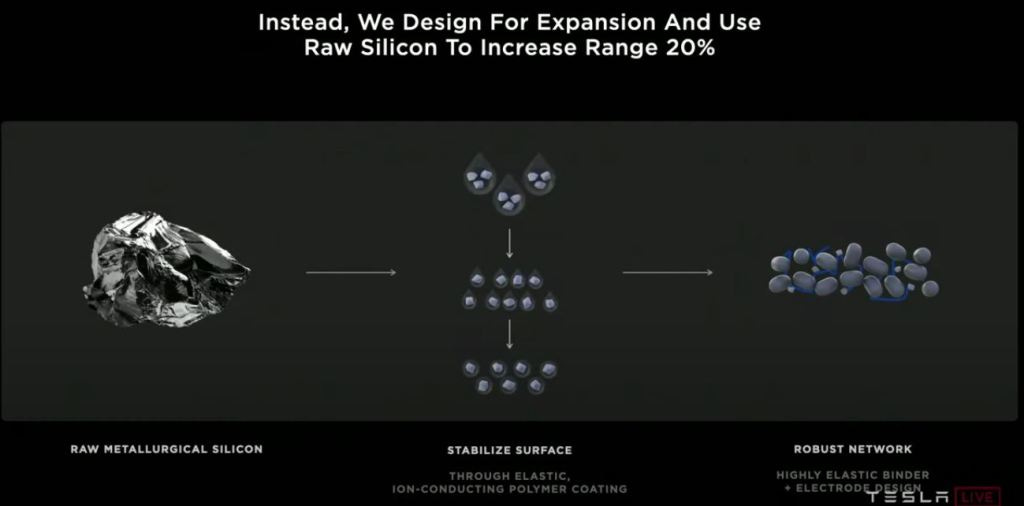

To boost energy density, Tesla proposed replacing most graphite with raw metallurgical silicon, which would help increase the range by 20% at a cost of only 1.20 USD/kWh of anode material. Since silicon changes its volume by up to 400% during charge-discharge cycles, its particles crack and lose electrical contact with each other. To mitigate this, Tesla proposed wrapping silicon in an ion-conductive polymer and using ‘‘elastic’’ binders (Figure 4).

Silicon was supposed to enable another 5% USD/kWh reduction at the battery pack level.

Vertical integration and recycling

The Battery Day outlined aggressive supply-chain integration: in-house cathode and battery production, lithium refining, and recycling.

High-nickel, cobalt-free cathodes would be used in premium vehicles, while lithium iron phosphate (LFP) would be used for mass-market vehicles and stationary storage. In addition, Tesla planned a lithium refinery to produce battery-grade lithium compounds.

Finally, recycling end-of-life cells to reuse valuable metals would close the battery supply loop and enable a 33% lithium cost reduction.

Altogether, this vertical integration was supposed to provide an additional 12% USD/kWh cost reduction at the pack-level.

Gigacasting and structural packs

Tesla proposed rethinking vehicle architecture by using massive ‘‘giga presses’’ to cast the front and rear of the car as single-pieces and use the battery pack itself as a structural floor (Figure 5). This promised reduced part count and cheaper assembly, resulting in an additional 7% USD/kWh reduction at the battery pack level.

Summing all of these reductions together, Tesla envisioned a 56% USD/kWh cost reduction at the battery pack level. We don’t know what was the exact reference that Tesla had in mind in 2020, but we know that the average EV battery pack price in 2020 was 126 USD/kWh. Assuming that ~20% of that is the margin, with a 56% cost reduction, Tesla was looking to manufacture battery packs at a cost of <50 USD/kWh (or <65 USD/kWh in today’s dollars).

The 2026 reality

Five years on, the Battery Day looks like a sharp lesson in manufacturing complexity:

4680 cells — partially successful

Tesla continues to scale 4680 production at Giga Texas, primarily for the Cybertruck, though the program has been defined by yield losses and mechanical issues. The reported “side dent” defect, where assembly pressure caused internal short risks, led to pack replacements. In fact, Tesla is still relying on Panasonic and LG Energy Solution for externally manufactured 4680 cells.

In December 2025 Tesla confirmed that 4680 cells will be returning in select Model Y vehicles as a hedge against global trade barriers, and possibly due to low demand for the Cybertruck. It would seem that this move is not due to the superiority of the produced 4680 cells, but mostly a consequence of the market and geopolitical realities.

The Q4 2025 shareholder update cites 40 GWh of production capacity installed at Giga Texas, yet we don’t know how much of that is actually used.

Dry electrode — partially successful

Tesla has successfully standardized dry anode coating for its 4680 production. The dry cathode, however, remained a primary bottleneck with early production lines reportedly suffering from scrap rates as high as 70–80% due to roller damage from brittle cathode powders.

However, on January 28, Tesla confirmed to have solved the dry cathode production and is currently at an early ramp stage, without mention of the actual production volumes. This is somewhat in disagreement with what Elon said at the Tesla Annual Shareholder Meeting in November 2025:

Yes. I guess the dry cathode, man, that’s turned out to be a lot harder than we thought. So I mean, it does look like it’s going to be successful, and it will have some cost advantage relative to wet cathode. But if I had to wind the clock back, I would probably have gone with wet cathode instead of dry cathode because it just turned out to be a lot harder to make it high capable of high volume production with super high reliability.

A reasonable conclusion is that Tesla is indeed capable of producing fully dry 4680 cells. But, they are not able to produce it at the necessary scale and yield to fully switch to a dry process. If this is correct, we could expect fully dry batteries only in certain high margin Tesla products.

There is also no mention of the continuous-motion 20 GWh production line, which hinged on a fully dry production of 4680 cells.

Silicon-rich anodes — unsuccessful

No Tesla vehicle to date uses silicon-rich anodes. Most teardowns of the 4680 cells revealed a primarily graphite anode. In fact, the long-promised 800 km Cybertruck ultimately launched with 550 km of range, partially due to the failure of silicon-rich anodes.

Looking forward, Tesla seems to have shifted its silicon strategy. Instead of chasing pure metallurgical silicon, Tesla is reportedly planning new cell variants (referred to as NC30/NC50) that will incorporate silicon-carbon composite blends.

Vertical integration and recycling — partially successful

Tesla has diversified cathode sourcing and expanded LFP usage, though in-house production remains limited. The Q4 2025 shareholder letter mentions that LFP production at Giga Nevada with CATL equipment is at an early ramp stage.2

One genuine success is the Corpus Christi lithium refinery, which began pilot operations in 2025 and refines spodumene into lithium hydroxide for use in cathode precursor production. This success could be a contributing factor to the reason L&F Co., a cathode supplier, slashed its supply deal with Tesla to under 10,000 USD (from 2.9B USD).

Giga Nevada’s recycling operations primarily handle manufacturing scrap, while end-of-life pack volumes are still too small to support a true circular supply loop.

There is no mention of high-nickel, cobalt-free cathodes.

Gigacasting and structural packs — successful

This is where Tesla’s manufacturing promise has largely materialized: gigacasting is now a cornerstone of the Model Y and Cybertruck platforms, enabled by a proprietary aluminum alloy that eliminates the need for post-casting heat treatment; a legitimate metallurgical breakthrough.

Nevertheless, while structural packs remain in production for the Cybertruck, Tesla disclosed that it is now integrating in-house 4680 cells into non-structural packs for certain Model Y variants, with the aim to simplify battery repairs by decoupling the cells from the vehicle’s primary chassis rigidity.

Tesla’s delivery

While battery pack prices have continued to decline, the actual pace has been slower than Tesla’s original cadence (Figure 6). By the end of 2025, average global pack prices for EVs fell to roughly 99 USD/kWh (or 81 USD/kWh in 2020 dollars), while being heavily weighted on the side of Chinese production output. Tesla’s battery cell production costs, while not public, are likely higher.

To reach Tesla’s original goal of a 56% reduction (<65 USD/kWh in today’s dollars), it would’ve had to fully deliver on its targets from the Battery Day. But that didn’t happen. The company aimed for 100 GWh of in-house dry cell production by now, while the actual output remains a fraction of that, estimated at ~20 GWh in early 2025 with unclear dry cell production amounts.3

Tesla only partially delivered on its promises and has done so with a significant delay. Its in-house battery production is nowhere near the scale and consistency that it requires and it still relies on external battery suppliers for the majority of its needs.

Ultimately, judging by Tesla’s strategic pivot into what Musk has described as ‘‘physical AI’’ and autonomy, it appears that it is not confident in its ability to deliver the Battery Day targets anymore.4

Putting it all into context

Tesla’s struggles do not exist in a vacuum. In fact, major industry players have been struggling with the same issues.

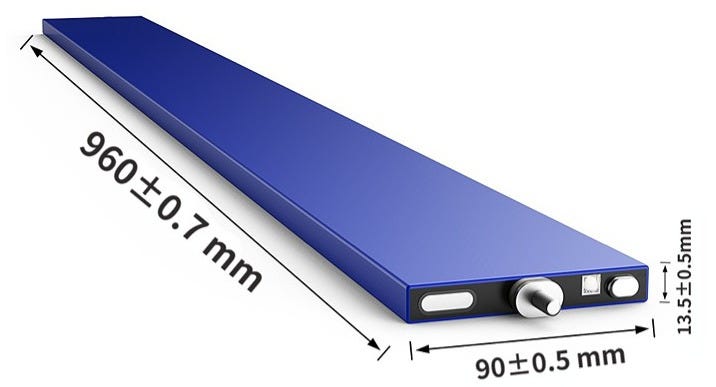

Large-format cylindrical cells remain a work in progress across the industry. Panasonic, LG Energy Solution, Samsung SDI, and others are pursuing similar designs. The Chinese manufacturers are arguably the most successful here, mostly because they favored large-format prismatic cells to make low-cost LFP viable at the pack-level with superior packaging (Figure 7).

On silicon anodes, companies like Amprius, Sila Nanotechnologies, Group14, as well as CATL and Samsung, are making progress, but none have yet achieved large-scale commercial deployment of silicon-rich anodes.

Dry electrode processing is likewise being pursued across the industry, with commercial timelines increasingly pushed into the late 2020s. Yield remains the bottleneck: without high yield, dry processing is not economical.

The bottom line is that Tesla has not uniquely failed and has made some important advances in battery technology. A valid criticism would be that announcing ambitious goals with unrealistic timelines betrays a lack of understanding of the complexity of battery manufacturing. Still, this overpromising is a standard Tesla practice that we have seen numerous times.

What to watch next?

Despite the partial delivery of the Battery Day targets, they show the direction Tesla is prioritizing and help pinpoint major focus points for the company.

Batteries are and will remain the cornerstone of Tesla products. Be it EVs, BESS, AI data centers, or humanoid robots, they all need batteries. Keeping an eye on these specific battery innovations is critical to understand Tesla’s future trajectory:

4680 dry production scale and cost: Can Tesla or its partners achieve volumes and yields that reduce system-level costs? Is dry coating working at scale for both anode and cathode? Do 4680 cells perform comparably or better than other formats? Cracking this, could be a major cost-saving innovation for Tesla, giving them unparalleled advantage in battery manufacturing.

Electrode innovation: Tesla has all but given up on developing in-house the metallurgical silicon anode. Still, silicon is the future of battery anodes and Tesla is likely keeping an eye on it. Can it deliver on the new silicon anode cells? What about the nickel-rich and cobalt-free cathodes? Whether Tesla decides to innovate in-house electrode designs or borrow them from third parties is key to understand their ambition here.

Vertical integration dynamics: A trend that has been under way in China for a while, it remains to be seen how successful Tesla will be with its in-house cathode production, lithium refining and recycling. Can Tesla successfully navigate the geopolitical realities and close the materials loop? This is critical if Tesla is to survive a major geopolitical event and continue daily manufacturing.

These three points would be key to understand if Tesla stays competitive in the coming years.

Industrialization as the ultimate arbiter of innovation

Tesla’s Battery Day vision was directionally correct and genuinely ambitious, but the hardest part, high-yield cell manufacturing, proved far more difficult than expected. The gap between promise and reality was not due to lack of effort, but because battery materials don’t scale linearly. Controlling material properties at scale is inherently difficult, and what works at pilot scale, doesn’t necessarily work at commercial scale. This gap explains why the 25,000 USD Tesla didn’t arrive as promised.

Battery innovation is always a two-step challenge. First, you need to conceptualize an innovation and then you need to show how you will manufacture such innovation at scale. Between these two steps is a valley of death that even Tesla struggles to cross.

If anything, the Battery Day was a reminder that in battery manufacturing, physics sets the schedule, not press events.

That’s all for now — until next time! 🔋

If you enjoyed this piece, consider sharing or subscribing to Lithium Horizons. It helps support future articles on materials powering the energy transition.

The ‘‘tabless’’ design isn’t exactly new. Saft experimented with similar designs back in 2000s. You can read the patent here: https://patents.google.com/patent/US20050008933.

Tesla has a goal of producing in-house around 7 GWh of LFP cells, however, Tesla’s annual EV production needs over 100 GWh.

Tesla’s Q4 2025 shareholder update mentions 40 GWh as installed capacity for 4680 cell production. This is the maximum production possible in one year, with the actual production numbers being unknown.

Tesla’s overall mission, as outlined in its Masterplan series, went from ‘‘Sustainable energy for all Earth’’ in 2023 to AI and sustainable abundance in 2025.